I am still processing what took place on February 15, 2016 at the Grammys. I don’t own a TV, by choice, but that day, I subscribed to the Network in order to stream the award show live. I was curious to see what type of performance Kendrick Lamar would present.

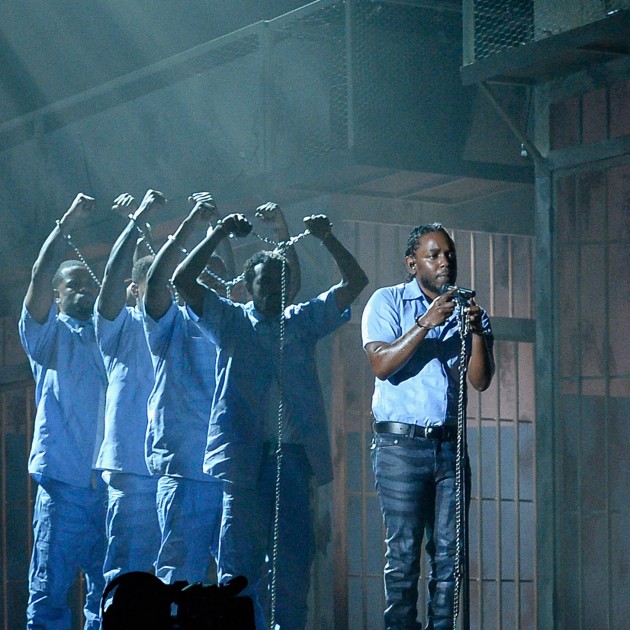

The performance opens up on a jail-like setting, four cells in which black men are locked up. One of them played a melancholic melody on the saxophone: the sound of Terrace Martin. You could also see black men out of these jail cells, in chains and shackles, walking up the stage in rhythm, led by the artist himself. At a time when black artists are seriously considering boycotting award shows due to the lack of diversity, Kendrick Lamar caused quite a stir by performing “The Blacker the Berry”, in a set that brings to mind middle passage of the slave trade. By staging such a painful chapter of American history, he chose to shine the spotlight on the black narrative and reclaim it on prime time National television. The jail décor echoed the slavery imagery embodied by the chains and shackles, suggesting that the mass incarceration of black males is a form of modern day slavery, with inmates’ underpaid labor benefitting big corporations.

Slavery imagery suggesting mass incarceration

The verse he chose to perform depicts quite a few stereotypes assigned to black men, “the bottom of mankind”, and the racial animosity that has been expressed towards coloreds for centuries. His verse is punctuated by the voice of reggae DJ Assassin singing the chorus and chanting: “every race start from the black, remember that”. The chorus comes as a liberation as all prisoners break free from their chains before entering in a dance trance by Krumping and Flexing. Anybody familiar with both dance styles would tell you that Krumping is a style which originated in LA and aims at channeling pain, rage and anger in a constructive way through dancing. Flexing, also known as Bone Breaking, consists in defying your body’s limits by performing extreme contortions. Both involve exorcising some type of pains, whether it is mental or physical.

In this short piece, we witness the display of Hip Hop at its greatest: MC with the chorus by DJ Assassin with a strong black message, Dancing, Graffiti with glow in the dark colors painted on the costumes; the DJ is replaced by a live band for the background music. What if Hip Hop was the last 40+ years’ gospel?

I can’t help but recall his acceptance speech for best rap album just a few minutes earlier, in which after thanking God, his parents, his fiancé, TDE and Top Dawg himself for taking him and his TDE colleagues out of “Compton … to be the best they could be”, he paid tribute to past classic Hip Hop albums and veterans: Ice Cube, Snoop’s “Doggystyle” and Nas’ “Illmatic”. He concluded by the following quote: “we will live forever, believe that”. Quite an ode to an art form which started from nothing.

African-looking village

The next setting is an African-looking village to perform “Alright”. We have everything from drums, dancers in traditional garments to a blazing fire – “next time” (a nod to James Baldwin maybe): back to Roots for a minute. This song seems to have become the hymn of Civil Rights Movement 2.0 all across America, as it was chanted during police harassment protests in Cleveland or during the 20th anniversary of the Million Man March, just to name a few occurrences. This song embodies a cry of hope for a community that has witnessed quite a few atrocities in the past few years. Scratch that, centuries. A new generation of activists can relate to Kendrick Lamar’s music and even use it as chants in a similar way “We Shall Overcome” was a rallying anthem to the African-American Civil Rights Movement.

References to the black struggles

In the last part of his performance, he is alone on stage and performs what seems to be a prayer or a contemplation on the night Trayvon Martin died:

“On February 26, I lost my life too (…) and for our community, do you know what it does? Add a trail of hatred, 2012 was taken from the world to see, set us back another 400 years, this is modern day slavery”. The performance goes full circle; we are back to square with a reflection on what the mass incarceration and killing of back people do to disseminate the black community.

The reality is, Kendrick Lamar’ repertoire contains numerous references to the black struggle: “Martin had a dream, Kendrick have a dream” (“Backseat Freestyle” in Good Kid, M.A.A.D City album. Or even in “HiiiPower” (Section.80” album), where he is referring to Huey P. Newton, Bobby Seale and Fred Hampton, just to name a few.

There is so much to say about this performance. His artwork has rekindled a lifetime conversation for generations to come. The more I listen to his music or watch his performances, the more I keep unfolding layers. Lamar has depth. His catalogue is a solid social commentary in a time where racial tensions and racialized discourse are even more present in the public eye. Mr. Lamar’s rap sparks essential questions within the black community, which leads to instilling pride, while still questioning its flaws. In my opinion, Kendrick Lamar’s latest album is part of the soundtrack of the Civil Rights Movement of this generation. And for this, I thank him.

The revolution is now being televised.